For more than a generation we have been living in a world of falling inflation. The combination of globalisation, a surge in the size of the global workforce, technology and falling union membership have crushed inflationary pressures. Some of these it can be argued, are starting to reverse, with demographic and globalisation trends particularly starting to shift. This, combined with record fiscal stimulus and a steep economic recovery from Coronavirus has meant that recent headlines have at least started to reignite interest in inflation, with Google searches for the word “inflation” in the US being the highest since they were first measured in 2004.

Over these past forty years, the narrative of company management has also largely been dominated by one view, the Friedman Doctrine, that the ‘social good’ of any company is to maximise profits for its shareholders. But much like those causes of deflation mentioned above, this narrative is being tested, with the importance of sustainability coming to the fore in how companies manage themselves and their impact on the world.

We are seeing the impact of deflation and the Friedman doctrine collide, as the low inflation environment we have experienced over the last few decades has come with wage and income inequality, which has had knock on political and social implications.

Going forward, the need for countries and companies to de-carbonise their production lines in the face of more extreme climate change may drive inflation higher, as paying for the externality of the race to the bottom in prices we have experienced over the last few decades finally becomes a climate emergency.

Income Inequality

Whilst there is debate over the causes the rise of income inequality over the past forty years, the fact that it has occurred is irrefutable.

We mentioned some of the key drivers in the introduction, but broadly what we have seen is a rise in outsourcing of manufacturing goods to lower income countries. China has experienced rapid population growth, technological advance, and social change, as people moved from agricultural villages to cities to seek work in the burgeoning manufacturing sector. This increase in the workforce, drove down labour costs and helped global companies develop goods at ever lower costs.

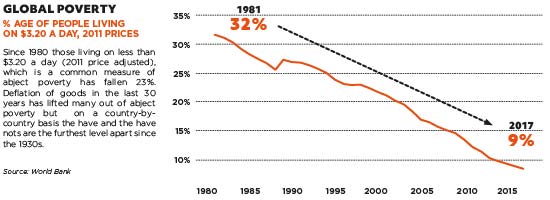

Globally, this meant GDP was re-distributed and it also meant that deflation of goods persisted. This helped reduce inequality between countries, lifting large swathes of the population of countries out of abject poverty. This has been one of the underreported triumphs of the last 30 years, brilliantly illustrated by Hans Rosling in the book Factfulness which highlights the marked improvement in quality of life for the average global citizen.

Trends of inequality are a key factor in sustainable investing

As the chart on the previous page illustrated, the world may be better off, but on a country-by-country basis the have and the have nots are the furthest level apart since the 1930s. The Gini coefficient which measures how evenly incomes are spread across populations continues to climb, highlighting how the lack of wage bargaining power, lack of unionisation and slow erosion of manufacturing jobs to external countries has affected wealth distribution. In addition, those that owned assets fared better through this period, with accommodative monetary policy fuelling asset price rises.

We feel that these trends of inequality are a very important factor in Sustainable investing. In governance terms, companies are increasingly required to disclose their gender pay gaps, their CEO to median employee pay and their policies regarding equal employment.

Companies that can best navigate this stark social upheaval and requirement for disclosure will fare best. This long-term trend may begin to reverse as geopolitics reduces globalisation and outsourcing trends and the policies of Joe Biden seek to try and push the US to a more equitable future.

The inflationary 'cost' of climate change

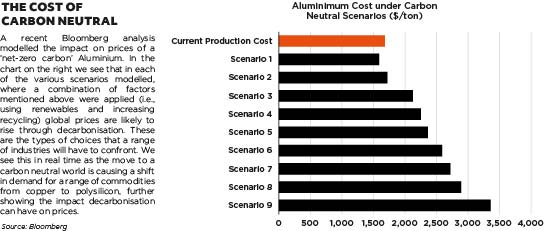

Governments have begun to recognise that they need to do much more to combat climate change. If they are to realise their goal of limiting temperature change to only 2 degrees Celsius by 2030 they will have to reduce carbon emissions by around 30% according to a study by Bloomberg.

The importance of climate action is being felt in every corner of the economy, industries from steel to autos are being left with little choice but to change how they make products and ultimately what they sell. This change in regulation and standards, as well as an admittance that for too long people have not been pricing the economic impact of carbon effectively will cause dramatic changes to supply chains. This in turn, could mean that these goods themselves cost more to produce.

Pricing these climate externalities has been something that has been economically unappealing until recently, as it could directly increase the costs of goods we use on a daily basis. However, with the advent of climate taxes and carbon credits that heavily polluting industries will have to accept, governments are beginning to explicitly price this cost.

Cleaning up the aluminium

Let’s take an example, Aluminium, a ubiquitous metal, used across a broad range of goods from “tin” foil to aircraft components. It is a highly energy intensive process to convert bauxite to the finished product, with smelting and refining both needing huge amounts of energy. Despite increases in efficiency and smelting technology, around half the energy used in this process still comes from coal power.

If the industry wants to clean up its act and move to a carbon neutral future, it will have to replace its energy suppliers to use renewables, increase recycling, and continue to invest in technology to produce aluminium more efficiently, to make up for these carbon emissions. Barring that, they can continue to pollute and purchase offsets, which governments have introduced to price the impact of pollution.

Conclusion

In conclusion, we can see that two forces have had an impact on the sustainable landscape as it stands today.

- Firstly, inequality has become extreme and as a result, social change is becoming ever more likely and companies are having to respond to this. No longer can companies claim to simply be profit maximising entities, instead they must respond to social change and take a stance on key issues such as inequality. The Friedman doctrine has now expanded such that companies must also be moral beings.

- Secondly, the price of goods currently fails to incorporate the true cost of carbon to the global economy. We see that industries are facing wide scale change and need to move away from high carbon to lower carbon production. This is being driven by government incentives as well as corporate and investor pressure, and this move could ultimately cause goods prices to rise over the medium term.

Please note the content of this article is provided for general information only. It is not intended to amount to advice, advisory, tax or other professional advice, consultation or service.

Although we make reasonable efforts to update the information on our site, we make no representations, warranties or guarantees, whether express or implied, that the content on our site is accurate, complete or up-to-date.